Words:

Carl Turner

Related Project:

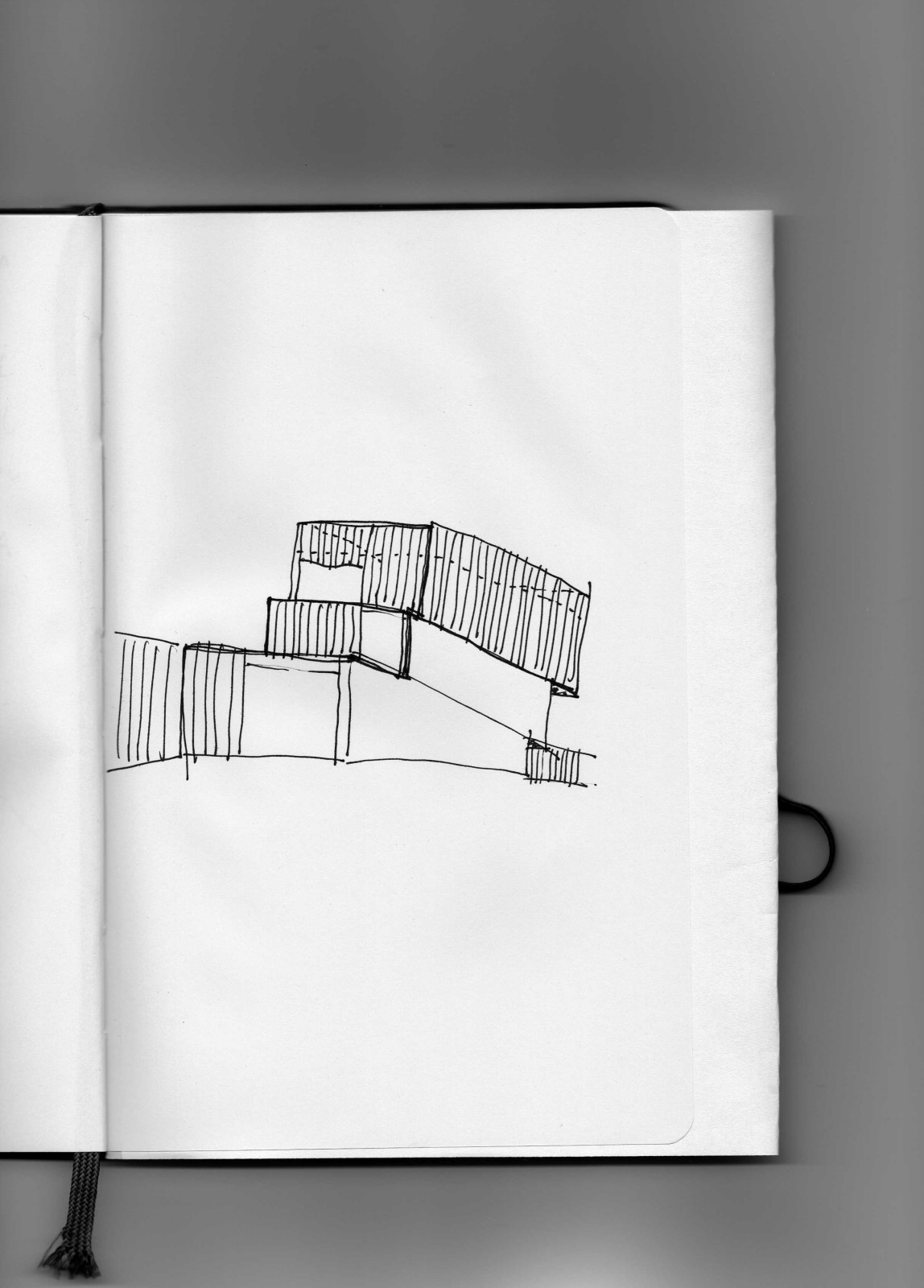

Slip House

Sketches:

Carl Turner

Photography:

Tim Crocker

Making good buildings requires more than good ideas. They take stamina, resilience and determination often bordering on blind-optimism, and never more so than when an architect attempts to build their own home. In 2006 Mary and I bought a house we didn’t want with the dream of building the house we did.

Mary and I stumbled across a 1930s terraced house for sale in 2006 and although we didn’t want the house, we noticed the long rear garden, had a quick look round and made an offer. Six weeks later we moved into a hovel–camping in one bedroom and cooking outside to avoid the rancid kitchen. Meanwhile we were busy working in Norfolk so life was full on. When the credit crunch hit it got a whole lot scarier.

Instead of imagining what planners might want, we presented them with what we wanted instead: an outstanding low energy, prototype terraced house (me_, serene, timeless and monastic (Mary), that could demonstrate that a new house could be beautiful (me). Referring to projects such as Borneo Sporenberg in Amsterdam, we showed how it could be the first in a terrace of exemplary but very different houses along its stretch of the street. Happily, the planners bought our vision and we were granted planning consent in 2008, before a painful three-year wait to finish projects elsewhere and raise the funds. Close to giving up, we finally got a mortgage and started on site in April 2011, working up the detailed design and project managing as we went along. Bringing in the Grand Designs crew didn’t exactly ease the pressure.

To make the house spatially and financially viable, we initially spent as little as possible and designed a flexible layout to allow us to sub-let or even sell part of the building in the future. As a practice we used it to learn more about low energy construction, exploring the fine line between a home and an experiment or passive bunker.

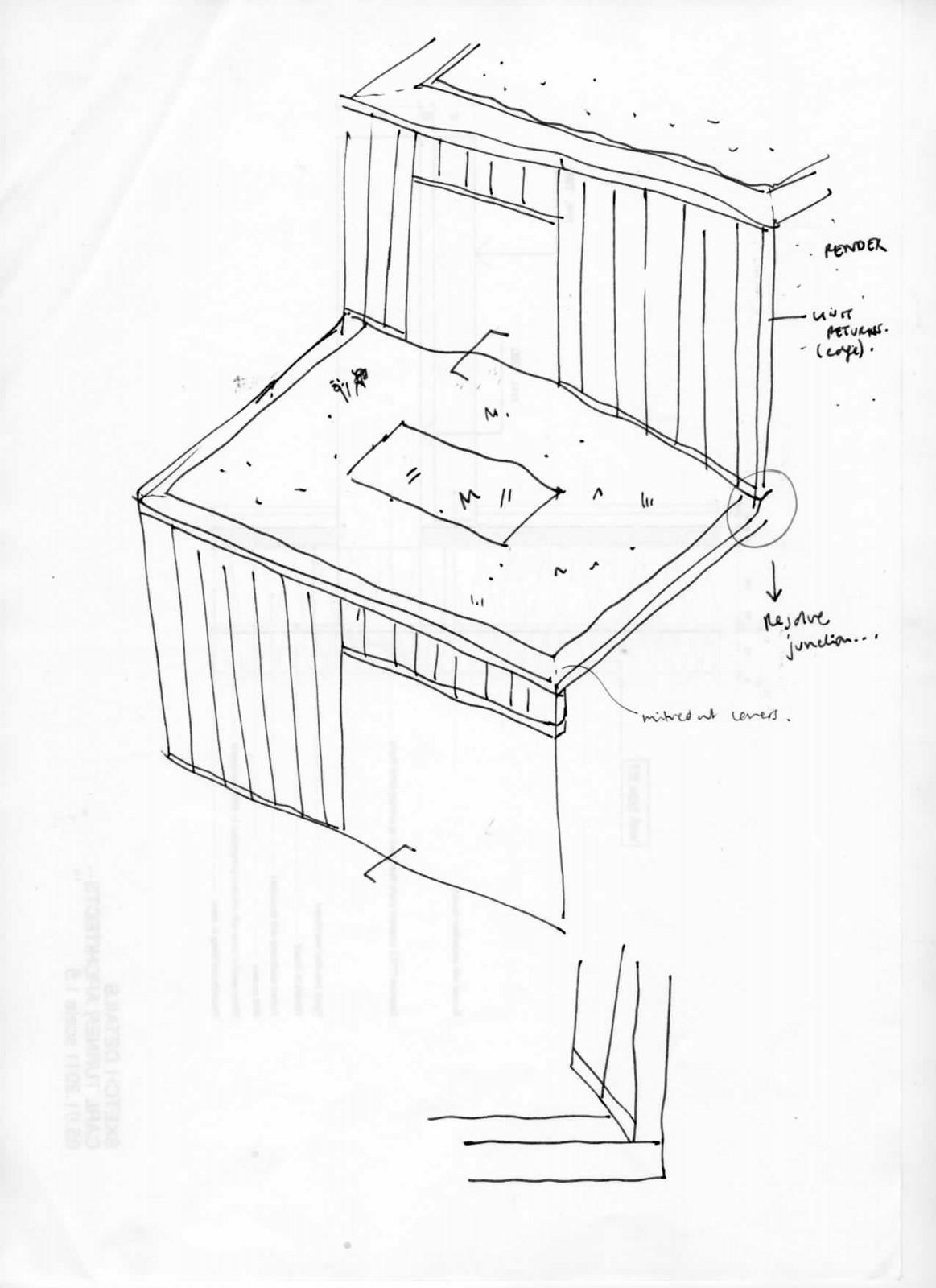

Slip House consists of three stacked boxes, pushed or slipped outwards from the back of the site towards the street. This avoids overshadowing houses to the rear and breaks up the bulk of the building, giving it a sculptural form. The is further exaggerated by the cast glass panels cantilevering about 1.75 meters above a concealed roof deck at the top of the building. The other elevations are similarly clad to maximise light into the building, give privacy and reduce overlooking. Depending upon the light, more or less of the diagonally braced structure can be seen through the milky glass cladding, further breaking up the volumes. Lower flank walls are simply finished with a white acrylic render, and small courtyards at the front and rear give the building a little breathing space.

The house was conceived as a hybrid in construction terms, employing as many off-site components as possible to speed up the build time and lessen the impact on the many neighbour. Initially we investigated the use of timber frame but this was discounted on structural grounds due to the open plan nature of the building, the cantilevers and the weight of the glass cladding. The steel frame was an engineering solution to provide a rigid braced frame keeping the floors clear of structure.

The frame sits onto a reinforced concrete slab with piled foundations, cast onto a recycled cardboard waffle clay heave board instead of polystyrene to reduce excavation and spoil. Insulated timber cassette panels |(200mm thick) were then simply slotted between the steel columns and beams to form perimeter walls and were fixed to blocks wedged and glued between the column flanges to provide a largely timber shell. Further insulation was then applied internally and externally to prevent cold bridging, and the interior face was lined with an airtight membrane through which no services or penetrations were allowed. An inner metal stud wall provided a service zone and painted plasterboard finish.

The pre-cast concrete floor deck system and stairs sit on plates welded to the steel beams. Further reinforced concrete containing heating pipes was laid on top, and we power floated the concrete topping to act as the floor finish. The floors not only give useful thermal mass but also help to give a solid acoustic.

Windows and roof lights were chosen for high thermal efficiency, and the large sliding doors are completely airtight when closed. These are painted white internally (good for U-values and performances) and faced externally with thin aluminium capping to last longer.

Code for Sustainable Homes certification and the need for a building warranty (to get a mortgage) forced us to use approved manufactures and subcontractors in a way we were unused to, making us think of the building more as a series of assembled parts. So for instance instead of integrating window frames into wall thicknesses, they were fully expressed as visible components. Their white finish determined that the rest of the interior should also be essentially white. Although the house has been referred to as minimalist, that wasn’t deliberate. Inexpensive white plastic switches and sockets are there because they need to be there. The frame is simply exposed rather than hidden. We think of it as an expressive rather than a minimalist building, playing on the qualities of both its structure and material characteristics.

The house is extremely energy efficient and designed to Code for Sustainable Homes Level 5, with a range of features including ‘energy piles’ |(heating coils inserted within ten of the foundation piles) utilising a solar-assisted ground-source heat pump to create a thermal store beneath the building; PVTs (solar thermal panels); a wildflower roof; rainwater harvesting for gardening, washing clothes and WCs; reduced water consumption; low energy lighting; mechanical ventilation with heat recovery within an airtight envelope; and massive level of insulation.

We are testing the building performance for three years. There were some operational issues over the first cold period with faulty electrical components–and some frustration at suppliers who may have the patter but none of the experience of living in a low energy house. Many also have an irritating assumption that any problems are human error. The house is preforming brilliantly–once the heating is turned off it takes a good 12 hours for the temperature to drop by a degree or two. However you have to get used to not opening the doors unless it’s 22 degrees outside.

After 15 months on site (with some down time in the early stages) ours is a light-filled, serene, peaceful and comfortable home which is still giving up its secrets. Having risked all to build it, we were very proud when it won a RIBA Award.